Introduction

Pneumonia, diarrhea, and malaria are among the leading causes of mortality in children younger than 5 years old.1 Effective therapies for these conditions exist,2 but children in poor rural communities often do not have access to formal healthcare,3,4 and coverage of these interventions remains low in many countries.5 Delivery of care through community health workers (CHWs) can increase coverage of specific treatments6–8 and lead to substantial reductions in child mortality.9–13 The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) recommend integrated community case management (iCCM) of pneumonia, diarrhea, and malaria.14 However, experience with large-scale implementation of iCCM remains limited. In 2010, just 12 countries in sub-Saharan Africa were implementing CCM of at least three illnesses, and only 6 sub-Saharan African countries were implementing CCM of at least three illnesses in at least 50% of the country's districts.15 Few rigorous assessments of iCCM implementation have been conducted, and the limited evidence on quality of care is mixed.16–22

As part of Ethiopia's Health Extension Program, over 30,000 female health extension workers (HEWs) have been trained for 1 year and deployed to communities throughout the country to provide preventive and curative health services. There are typically two HEWs assigned to a kebele (subdistrict) with a population of approximately 5,000 people. HEWs usually provide clinical care in health posts but may also provide care in the homes of community members.

After a national policy change supporting community-based treatment of childhood pneumonia by HEWs in early 2010, Ethiopia has scaled up iCCM provided by HEWs in most regions of the country. Antibiotic therapy (with cotrimoxazole) for pneumonia and zinc for treatment of diarrhea have been added to the pre-existing CCM (routine CCM) program, which included management of childhood diarrhea (with oral rehydration salts [ORS] only), malaria, malnutrition, measles, ear infection, and anemia. Other than the addition of antibiotics and zinc, the iCCM program provides a number of program supports, including a 6-day training for HEWs on iCCM, strengthened supervision, improved supply chain management for essential commodities, and enhanced monitoring and evaluation. Definitions of key terms are shown in Box 1.

Box 1 Definitions of key terms

The scale-up of iCCM was implemented in a phased manner in Oromia Region. This allowed for randomization of rural woredas (districts) in two zones into phase one intervention areas (iCCM) and phase two comparison areas (routine CCM) for an independent evaluation of the impact of iCCM. In addition to the present study, data for the evaluation came from baseline and endline household surveys to measure child mortality and coverage of treatments for common childhood illnesses.

This study was commissioned by UNICEF to assess whether iCCM implementation strength, quality of care, and use of services were sufficient to plausibly expect a substantial impact from the intervention on child mortality at the population level. We conducted a cross-sectional survey of health posts where HEWs work in intervention and comparison areas. The study had two main objectives: (1) measure and compare indicators of iCCM implementation strength in intervention areas and routine CCM implementation strength in comparison areas and (2) assess the quality of iCCM services provided to sick children in intervention areas. Quality of care was not assessed in comparison areas because the primary purpose of the study was to assess implementation strength and quality of care of iCCM; also, funding for data collection in comparison areas was limited.

This survey was the first to evaluate the scale-up of iCCM in Ethiopia and the first rigorous assessment of the quality of care provided by iCCM-trained HEWs. It was also one of the first studies to assess the quality of iCCM services in sub-Saharan Africa and the first study to assess integrated management of childhood pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, and malnutrition by CHWs.

Materials and Methods

Study population.

The survey was conducted in rural areas of Jimma and West Hararghe Zones of Oromia Region. Oromia is Ethiopia's largest region, with approximately 30 million people.23 Eighty-three percent of the population lives in rural areas, and the primary occupation is subsistence agriculture.24 Malaria risk varies in the study areas, with about one-quarter of health posts in high-malaria risk areas, 25% with no malaria, and the rest with low malaria risk. The study was conducted just before the start of the rainy, high-malaria transmission season. Jimma and West Hararghe Zones have populations of approximately 2.9 and 2.1 million people, respectively.25

Survey design and inclusion criteria.

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of rural health posts in the two study zones. The sample was stratified by iCCM intervention and comparison areas. Intervention areas received the iCCM program detailed above, whereas comparison areas continued with the pre-existing routine CCM program. Table 1 details the differences between the iCCM and the routine CCM programs. Systematic random sampling was used to select health posts within each stratum.

Comparison of case management guidelines and program inputs for the Ethiopia iCCM program and routine CCM

| ICCM (intervention areas) | Routine CCM (comparison areas) | |

|---|---|---|

| Management of iCCM illnesses for children 2–59 months | ||

| Pneumonia | Cotrimoxazole | Referral to health center |

| Severe pneumonia | Pre-referral treatment with cotrimoxazole; referral to health center | Referral to health center |

| Diarrhea (some dehydration, no dehydration) | ORS/ORT; zinc | ORS/ORT |

| Severe diarrhea (severe dehydration, persistent diarrhea, severe persistent diarrhea, dysentery) | ORS; vitamin A (for persistent and severe persistent diarrhea only); referral to health center | ORS; vitamin A (for persistent and severe persistent diarrhea only); referral to health center |

| Malaria | Antimalarial | Antimalarial |

| Severe febrile disease | Pre-referral treatment with cotrimoxazole; referral to health center | Referral to health center |

| Uncomplicated malnutrition | RUTF or supplementary feeding program | RUTF or supplementary feeding program |

| Severe complicated malnutrition | Pre-referral treatment with amoxicillin and vitamin A; referral to health center | Pre-referral treatment with amoxicillin and vitamin A; referral to health center |

| Measles | Vitamin A | Vitamin A |

| Severe complicated measles | Vitamin A; cotrimoxazole; tetracycline eye ointment (optional); referral to health center | Vitamin A; tetracycline eye ointment (optional); referral to health center |

| Measles with eye or mouth complications | Vitamin A; tetracycline eye ointment (optional); gentian violet (optional) | Vitamin A; tetracycline eye ointment (optional); gentian violet (optional) |

| Acute ear infection | Paracetamol; referral to health center | Paracetamol; referral to health center |

| Anemia | Referral to health center | Referral to health center |

| Program inputs | ||

| Training | 6 days of training on iCCM | No additional training |

| Supervision | Standardized supportive supervision on iCCM supported by partner NGOs plus standard government supervision; biannual PRCM meetings | Standard government supervision |

| Supply of commodities | Support for purchase and supply of drugs and other commodities by UNICEF and partners; provision of iCCM registers, iCCM chart booklets, timers, and other supplies | Standard government commodity supply chain system; no additional supplies or job aids |

| Monitoring and evaluation | Enhanced data collection during supervisions and PRCM meetings; data management support by UNICEF | Standard government monitoring and evaluation |

NGO = non-governmental organization; ORT = oral rehydration salts; PRCM = performance review and clinical mentoring; RUTF = ready-to-use therapeutic food.

All HEWs present and providing case management services in selected health posts were included. Children had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) 2–59 months of age (children younger than 2 months of age were excluded because there are separate clinical guidelines for this age group that call for referral to a health facility for most cases; also, we expected an extremely small sample of children in this age group, which would not justify the extra expense of training data collectors on the algorithm for children younger than 2 months of age), (2) having at least one complaint consistent with an eligible iCCM illness, and (3) initial consultation for the current illness episode.

Sample size.

We selected 104 health posts from intervention areas and 46 health posts from comparison areas. Proportions of the indicators were assumed to be 50% to give the most conservative sample size. Confidence was set at 95%. We adjusted for non-response of 5% for health posts, 5% for HEWs, and 10% for patients. A design effect of 1.3 was included to account for clustering of HEWs and patients in health posts. Assuming an average of 1.5 HEWs per health post, 104 health posts allowed for estimates of health post- and HEW-level indicators in intervention areas with a precision of ±10% points. Assuming two sick children per health post, primary patient-level indicators would have a precision of ±9% points. The smaller sample size in comparison areas allowed a precision of ±15% points for health post- and HEW-level indicators.

Instruments and indicators.

The survey instruments and primary indicators of implementation strength and quality of care were adapted from the WHO Health Facility Survey tool,26 a survey of Health Surveillance Assistants in Malawi,21 and the CCM Global Indicators.27 Indicator definitions are presented in Supplemental Appendix 1.

Data collection.

Data were collected in May and June of 2012, about 1 year after completion of training of HEWs in iCCM and the beginning of iCCM implementation in the intervention areas. Data collectors were health professionals who had worked as iCCM trainers or supervisors. Survey personnel were trained for 7 days, and all observers and re-examiners achieved at least 90% concordance with gold standard clinicians on three consecutive role play examinations. Data collectors were sent to woredas in which they did not normally work to avoid biasing the results.

Assessment of program implementation strength.

In intervention and comparison areas, survey teams collected information on the strength of iCCM/routine CCM implementation. Data collectors inspected iCCM commodities, supplies, and job aids. Next, they conducted interviews with the HEWs to learn about training and supervision received as well as HEW characteristics. Finally, they recorded information on sick child consultations from patient registers.

Assessment of quality of care.

The assessment of quality of care was conducted in intervention areas only. HEWs were notified of upcoming study visits and asked to mobilize caretakers to bring sick children to the health post on the day of the survey team visit. If fewer than two children presented at the health post within 1 hour of the health post opening, the team supervisor, along with an HEW or community volunteer, recruited sick children from nearby households. Eligible children received a consultation from an HEW while a data collector silently observed and recorded details of the HEW's assessment, classification, treatment, referral, and counseling. Next, the observer took the patient and caretaker away from the HEW and asked the caretaker to explain how they would administer any treatments prescribed for the child. Finally, the re-examiner performed a consultation with the patient and caretaker using a re-examination form that followed Ethiopia iCCM clinical guidelines.

Data analysis.

Data were entered directly into tablet computers using the Open Data Kit (ODK)28 as the data capture software and stored in a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database.29 All analyses were carried out in Stata 12.30 Descriptive statistics comprising proportions or means were calculated for selected indicators. Standard errors and associated 95% confidence intervals for HEW- and patient-level variables were calculated using the Taylor linearization method to account for clustering within health posts.31 Indicators of correct classification or treatment were calculated by comparing the HEW's classification and treatment with the gold standard classification from the re-examination and the associated treatments/referral recommended in the iCCM clinical guidelines. We performed clinical pathways analyses stratified by children with severe and uncomplicated illness to identify where case management errors occurred during assessment, classification, treatment, and referral of sick children.32,33 The full research protocol and study instruments are available online.34

Ethical considerations.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of the Oromia Regional Health Bureau and the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health. Informed oral consent was obtained from all HEWs and caretakers of sick children. Written consent from all participants would not have been possible because many of the participants were not literate. The IRBs approved the use of oral consent, and data collectors noted on a form whether oral consent was obtained from each participant.

Results

One health post in the intervention areas was excluded, because it was closed indefinitely, giving 103 health posts in intervention areas and 46 health posts in comparison areas that were successfully surveyed. All HEWs encountered in health posts were included in the study, resulting in samples of 137 HEWs in intervention areas and 64 HEWs in comparison areas. In total, 257 children were included in intervention areas.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the HEWs included in the sample. They were all women, and HEWs in both study arms had an average of about 4 years of experience as an HEW; 91% of HEWs in intervention areas and 86% of HEWs in comparison areas reported living in the same kebele in which they work. However, only 12% of HEWs in intervention areas and 6% of HEWs in comparison areas reported having lived in the kebele in which they work before beginning their initial HEW training, indicating that most HEWs were not selected from the communities in which they work.

Distribution of HEWs by selected characteristics in intervention (N = 137) and comparison (N = 64) areas in Jimma and West Hararghe Zones, Oromia Region, Ethiopia in 2012

| Characteristic | Intervention areas | Comparison areas | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percent | n | Percent | |

| Age, years | ||||

| 18–20 | 13 | 9.5 | 9 | 14.1 |

| 21–23 | 83 | 60.6 | 35 | 54.7 |

| 24–26 | 35 | 25.6 | 18 | 28.1 |

| 27–29 | 4 | 2.9 | 1 | 1.6 |

| 30–32 | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 80 | 58.4 | 39 | 60.9 |

| Single | 56 | 40.9 | 25 | 39.1 |

| Separated/divorced | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| HEW lives in the same kebele as health post | 125 | 91.2 | 55 | 85.9 |

| HEW lived in the kebele 1 year before completing basic HEW training | 16 | 11.7 | 4 | 6.3 |

Table 3 presents the characteristics of sick children in the sample. According to the gold standard classifications, diarrhea (66%), pneumonia (15%), malnutrition (13%), and ear infection (12%) were the most common illnesses. Few children presented with malaria (1%), measles (2%), or anemia (4%). Spontaneous consultations accounted for only 18% of the sample of children; 37% of children were mobilized by the HEWs, and active recruitment of sick children accounted for 45% of the sample.

Distribution of sick children by selected characteristics in intervention areas in Jimma and West Hararghe Zones, Oromia Region, Ethiopia in 2012 (N = 257)

| Characteristic | n | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age, months | ||

| 2–11 | 94 | 36.6 |

| 12–23 | 92 | 35.8 |

| 24–35 | 39 | 15.2 |

| 36–47 | 22 | 8.6 |

| 48–59 | 10 | 3.9 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 129 | 50.2 |

| Female | 128 | 49.8 |

| Gold standard disease classifications | ||

| Pneumonia | 39 | 15.2 |

| Diarrhea | 169 | 65.8 |

| Malaria/severe febrile disease | 3 | 1.2 |

| Measles | 5 | 2.0 |

| Malnutrition | 32 | 12.5 |

| Ear infection | 30 | 11.7 |

| Anemia | 11 | 4.3 |

| Severe illness | 38 | 14.8 |

| Needs referral* | 63 | 24.5 |

| Method of recruitment | ||

| Spontaneous | 45 | 17.5 |

| Mobilized by HEWs | 96 | 37.4 |

| Recruited by survey team | 116 | 45.1 |

In addition to severe illnesses, acute ear infection and anemia require referral.

Program implementation strength.

Table 4 shows the proportion of HEWs that received training and the proportion of health posts that received supervision in intervention and comparison areas. Nearly all HEWs (98%, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 93–99) in the intervention areas received the iCCM training. HEWs in 87% (95% CI = 79–93) of health posts received at least one supervision visit related to iCCM in the previous 3 months, and 85% (95% CI = 77–91) of health posts received supervision that included clinical reinforcement (observation of consultations or register review with feedback). As expected, no HEWs in comparison areas had received the iCCM training. Only 43% (95% CI = 28–59) of health posts in comparison areas had been supervised on routine CCM in the previous 3 months, and 19% (95% CI = 9–34) of health posts received supervision with clinical reinforcement.

Selected indicators of training and supervision in intervention and comparison areas in Jimma and West Hararghe Zones, Oromia Region, Ethiopia in 2012

| Indicator | Intervention areas | Comparison areas | P value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N* | Percent (95% CI) | N | Percent (95% CI) | ||

| HEW trained in iCCM | 137 | 97.8 (93.3–99.3) | 64‡ | 0.0 | < 0.001 |

| Health post received supervision on iCCM/routine CCM in the previous 3 months | 100§ | 87.0 (78.8–92.9) | 42¶ | 42.9 (27.7–59.0) | < 0.001 |

| Health post received supervision on iCCM/routine CCM that included register review or observation of consultations in the previous 3 months | 100§ | 85.0 (76.5–91.4) | 42¶ | 19.1 (8.6–34.1) | < 0.001 |

| HEW received instruction in iCCM/routine CCM clinical practice at a health center in the previous 3 months | 137 | 57.7 (48.8–66.0) | 64 | 7.8 (3.1–18.3) | < 0.001 |

Number of HEWs or health posts eligible for indicator.

Two-sample binomial test of difference in proportions between intervention and comparison areas.

HEWs in comparison areas were not expected to be trained in iCCM, and therefore, this result confirms that there was little to no spillover of iCCM training to HEWs outside of the intervention areas.

Three health posts were excluded, because HEWs reported not being present for the majority of the previous 3 months.

Four health posts were excluded, because HEWs reported not being present for the majority of the previous 3 months.

Table 5 presents the proportions of health posts with key iCCM/routine CCM commodities, supplies, and job aids on the day of data collection and health posts with no stockout of more than 7 consecutive days in the previous 3 months in intervention and comparison areas; 69% (95% CI = 59–78) of intervention health posts had all seven essential commodities for iCCM on the day of data collection. The proportion of health posts with individual items in stock ranged from 99% (cotrimoxazole) to 80% (ready-to-use therapeutic food). Only 4% (95% CI = 1–15) of health posts in comparison areas had all five essential commodities for routine CCM in stock. About one-half (52%, 95% CI = 42–61) of health posts in intervention areas and all health posts in comparison areas reported a stockout lasting longer than 7 consecutive days in the previous 3 months of at least one of the essential items. Just under one-half (46%, 95% CI = 36–56) of intervention health posts and no comparison health posts had all essential supplies and job aids in stock on the day of the visit. Nearly all indicators of implementation strength were significantly higher in intervention areas than comparison areas.

Availability of essential iCCM/routine CCM commodities, supplies, and job aids on the day of data collection and no stockout of essential commodities in the 3 months preceding the survey in intervention (N = 103) and comparison (N = 46) areas in Jimma and West Hararghe Zones, Oromia Region, Ethiopia in 2012

| Item | Available on day of data collection | No stockout > 7 days in the last 3 months | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention areas | Comparison areas | P value* | Intervention areas | Comparison areas | P value | |||||

| n | Percent (95% CI) | n | Percent (95% CI) | n | Percent (95% CI) | n | Percent (95% CI) | |||

| All essential commodities for iCCM/routine CCM† | 71 | 68.9 (59.1–77.7) | 2 | 4.4 (0.5–14.8) | < 0.001 | 53 | 51.5 (41.4–61.4) | 0 | 0.0 | < 0.001 |

| Cotrimoxazole‡ | 102 | 99.0 (94.7–100) | 1 | 2.2 | < 0.001 | 102 | 99.0 (94.7–100) | 2 | 4.4 (0.5–14.8) | < 0.001 |

| ORS | 100 | 97.1 (91.7–99.4) | 28 | 60.9 (45.4–74.9) | < 0.001 | 93 | 90.3 (82.9–95.2) | 28 | 60.9 (45.4–74.9) | < 0.001 |

| Zinc‡ | 99 | 96.1 (90.4–98.9) | 0 | 0.0 | < 0.001 | 83 | 80.6 (71.6–87.7) | 0 | 0.0 | < 0.001 |

| ACT | 91 | 88.4 (80.5–93.8) | 23 | 50.0 (34.9–65.1) | < 0.001 | 90 | 87.4 (79.4–93.1) | 26 | 56.5 (41.1–71.1) | < 0.001 |

| Chloroquine | 92 | 89.3 (81.7–94.5) | 17 | 37.0 (23.2–52.5) | < 0.001 | 91 | 88.4 (80.5–93.8) | 18 | 39.1 (25.1–54.6) | < 0.001 |

| RUTF | 82 | 79.6 (70.5–86.9) | 16 | 34.8 (21.4–50.2) | < 0.001 | 80 | 77.7 (68.4–85.3) | 14 | 30.4 (17.7–45.8) | < 0.001 |

| RDT | 92 | 89.3 (81.7–94.5) | 29 | 63.0 (47.5–76.8) | < 0.001 | 91 | 88.4 (80.5–93.8) | 29 | 63.0 (47.5–76.8) | < 0.001 |

| All essential supplies and job aids for iCCM/routine CCM§ | 47 | 45.6 (35.8–55.7) | 0 | 0.0 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Functional timer | 94 | 91.3 (84.1–95.9) | 5 | 10.9 (3.6–23.6) | < 0.001 | |||||

| Thermometer | 82 | 79.6 (70.5–86.9) | 30 | 65.2 (49.8–78.6) | 0.06 | |||||

| Weighing scale | 79 | 76.7 (67.3–84.5) | 37 | 80.4 (66.1–90.6) | 0.612 | |||||

| MUAC tape | 102 | 99.0 (94.7–100) | 41 | 89.1 (76.4–96.4) | 0.005 | |||||

| Clean water | 74 | 71.8 (63.0–80.7) | 3 | 6.5 (1.4–17.9) | < 0.001 | |||||

| Supplies for ORS¶ | 77 | 74.8 (65.2–82.8) | 0 | 0.0 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Chart booklet with clinical guidelines | 103 | 100 | 0 | 0.0 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Sick child register | 103 | 100 | 7 | 15.2 (6.3–28.9) | < 0.001 | |||||

ACT = artimisinin-based combination therapy; MUAC = middle upper arm circumference; RDT = rapid diagnostic test (malaria).

Two-sample binomial test of difference in proportions between intervention and comparison areas.

Intervention areas: cotrimoxazole, ORS, zinc, ACT, chloroquine, RUTF, and RDT. Comparison areas: ORS, ACT, chloroquine, RUTF, and RDT.

Cotrimoxazole and zinc were not part of the routine CCM program, and therefore, comparison health posts are not expected to have these drugs available.

Intervention areas: timer, thermometer, weighing scale, MUAC, clean water, supplies for ORS, iCCM chart booklet, and sick child register. Comparison areas: timer, thermometer, weighing scale, MUAC, clean water, supplies for ORS, and sick child register.

Cup and spoon.

Quality of care.

Table 6 presents key indicators of quality of care in intervention areas. HEWs completed an average of 9.2 of 11 key assessment tasks. A large majority of children (81%, 95% CI = 74–86) was assessed for the presence of cough, diarrhea, fever, and malnutrition. Fewer children (62%, 95% CI = 53–70) were assessed for all four general danger signs. Just over one-half of children (53%, 95% CI = 46–60) were correctly classified for all major iCCM illnesses.

Selected indicators of quality of case management by HEWs in intervention areas in Jimma and West Hararghe Zones, Oromia Region, Ethiopia in 2012

| Indicator | N* | Percent | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | |||

| Child assessed for four general danger signs | 257 | 61.9 | 52.5–70.4 |

| Child checked for presence of cough, diarrhea, fever, and malnutrition | 257 | 80.5 | 73.6–86.0 |

| Child with cough or difficult breathing assessed for fast breathing by counting of respiratory rate | 148 | 93.2 | 85.8–96.9 |

| Child's vaccination status checked (children under 12 months) | 94 | 97.9 | 91.7–99.5 |

| Child's respiratory rate counted by the HEW within ± five breaths of the gold standard | 130 | 70.0 | 60.8–77.8 |

| Classification | |||

| Child correctly classified for all major iCCM illnesses | 257 | 52.9 | 45.6–60.1 |

| Child not up to date on immunizations classified as not up to date | 77 | 36.4 | 26.1–48.1 |

| Treatment and referral | |||

| Child correctly treated† and/or referred for all major iCCM illnesses | 257 | 64.2 | 57.4–70.5 |

| Child with pneumonia correctly treated for pneumonia | 39 | 71.8 | 55.8–83.7 |

| Child with diarrhea correctly treated for diarrhea | 169 | 79.3 | 71.5–85.4 |

| Child with malnutrition correctly treated for malnutrition | 32 | 59.4 | 40.4–76.0 |

| Child with malaria correctly treated for malaria | 3 | 66.7 | 2.0–100 |

| Child with measles correctly treated for measles | 5 | 20.0 | 0.3–94.9 |

| Child with severe illness correctly treated and/or referred | 38 | 34.2 | 21.5–49.7 |

| Child needing referral correctly referred | 63 | 54.0 | 40.7–66.7 |

| Child received first dose of all needed treatments in the presence of the HEW‡ | 163 | 13.5 | 8.4–21.0 |

| Child needing vitamin A supplementation received vitamin A | 66 | 18.2 | 9.9–31.0 |

| Child needing mebendazole received mebendazole | 30 | 20.0 | 9.0–38.8 |

| Child received an unnecessary antibiotic | 257 | 5.5 | 3.0–9.7 |

| Child received an unnecessary antimalarial | 257 | 0.0 | – |

| Counseling | |||

| Caretaker received demonstration of how to administer all treatments by the HEW‡ | 160 | 74.4 | 63.4–82.9 |

| Caretaker correctly described how to give all treatments‡ | 156 | 83.3 | 75.5–89.0 |

| Caretaker advised to give extra fluids and continued feeding for diarrhea§ | 140 | 85.0 | 77.7–90.2 |

| Caretaker advised to return immediately if the child cannot drink/breastfeed or becomes sicker§ | 213 | 36.2 | 27.3–46.0 |

| Caretaker advised on when to return for follow-up§ | 213 | 93.4 | 88.0–96.5 |

Number of children eligible for task.

Includes prescription with correct dose, duration, and frequency.

Includes cotrimoxazole, ORS, zinc, vitamin A, ACT, chloroquine, and amoxicillin and excludes children who were referred.

Excludes children who were referred.

Nearly two-thirds of children (64%, 95% CI = 57–71) were correctly managed for all major iCCM illnesses. HEWs correctly treated 72% (95% CI = 56–84) of children with pneumonia, 79% (95% CI = 72–85) of children with diarrhea, and 59% (95% CI = 40–76) of children with malnutrition. Sample sizes of children with malaria and measles were too small to draw meaningful conclusions about management of those illnesses. Only 6% (95% CI = 3–10) of children received an antibiotic when it was not indicated, and no children received an unnecessary antimalarial. Just 34% (95% CI = 22–50) of children with severe illness were correctly managed, and HEWs referred about one-half (54%, 95% CI = 41–67) of children needing referral to a health center. Among 13 children with severe illness who were not referred, 8 (62%, 95% C= 31–85) children received correct treatment for their illnesses (excluding the requirement to refer). Furthermore, few children (14%, 95% CI = 8–21) received the first dose of all needed treatments in the presence of the HEW. Only 18% (95% CI = 10–31) of children needing a vitamin A supplement received vitamin A, and 20% (95% CI = 9–39) of children needing deworming medication received mebendazole. Over three-quarters of caretakers (74%, 95% CI = 63–83) received a demonstration on how to administer all treatments by the HEW, and 83% (95% CI = 76–89) of caretakers correctly described how to give all treatments.

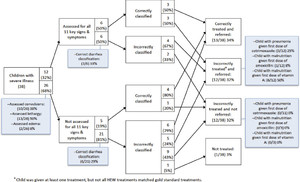

Figures 1 and 2 present analyses of clinical errors for children with uncomplicated illness only and children with at least one severe illness in intervention areas, respectively. Around one-third of children were assessed for all 11 selected signs and symptoms of iCCM illnesses. The most common assessment errors were failures to assess convulsions, edema, and lethargy. Incorrect classification of pneumonia was the most common classification error for children with uncomplicated illness, partially because of incorrect assessment of fast breathing. The most common treatment errors were failure to give cotrimoxazole to children with pneumonia and failure to give ORS for diarrhea, although these items were in stock. Misclassification was common among children with severe illness, and incorrect treatment was common regardless of whether children were correctly classified. The most common treatment errors for children with severe illness were failure to give the first dose of cotrimoxazole for pneumonia, failure to give the first doses of amoxicillin and vitamin A for severe complicated malnutrition, and not referring children to health centers when it was required.

Clinical errors analysis for children with uncomplicated illnesses in intervention areas in Jimma and West Hararghe Zones, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. ORT = oral rehydration therapy.

Citation: The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 91, 2; 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0751

Clinical errors analysis for children with at least one severe illness in intervention areas in Jimma and West Hararghe Zones, Oromia Region, Ethiopia.

Citation: The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 91, 2; 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0751

Use and service provision.

Table 7 presents the mean number of sick child consultations per health post in the previous 1 month and selected indicators of service provision in intervention and comparison areas. Intervention health posts saw an average of 16 (95% CI = 13–19) sick children in the previous 1 month (range = 0–95) compared with 5 (95% CI = 2–8) sick children seen in comparison health posts (range = 0–32). Virtually no children under 2 months of age were seen in intervention or comparison areas.

Mean number of sick child consultations per health post and selected indicators of service provision in intervention and comparison areas in Jimma and West Hararghe Zones, Oromia Region, Ethiopia in 2012

| Indicator | Intervention areas | Comparison areas | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | Range | Mean (95% CI) | Range | |

| Sick child consultations in previous 1 month | ||||

| Total | 16.0 (13.2–18.8) | 0–95 | 5.0 (2.3–7.7) | 0–32 |

| 0 to < 2 months | 0.3 (0.1–0.5) | 0–9 | 0.03 (0.0–0.1) | 0–1 |

| 2–59 months | 15.7 (13.0–18.4) | 0–94 | 5.0 (2.4–7.6) | 0–31 |

| Female | 8.0 (6.6–9.5) | 0–40 | 2.3 (0.7–3.9) | 0–19 |

| Male | 7.9 (6.4–9.4) | 0–57 | 2.4 (1.2–3.7) | 0–13 |

| Unspecified | 0.1 (0.0–0.1) | 0–4 | 0.3 (0.0–0.7) | 0–6 |

| Hours health post was open in previous 1 week | 23.3 (21.0–25.5) | 0–40 | 20.2 (17.0–23.5) | 0–40 |

| Hours spent by the HEW in the previous 1 day | ||||

| Providing clinical services in the health post | 4.0 (3.5–4.5) | 0–10 | 1.8 (1.1–2.5) | 0–8 |

| Providing clinical services in the community | 0.5 (0.3–0.6) | 0–7.5 | 0.8 (0.3–1.2) | 0–5 |

| Community education/mobilization; disease prevention | 0.9 (0.6–1.1) | 0–8 | 1.5 (0.9–2.2) | 0–8 |

| Other health-related activities | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0–8 | 1.4 (0.7–2.1) | 0–8 |

| Other non–health-related activities | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0–8 | 0.4 (0.1–0.8) | 0–7 |

| Travel outside kebele | 0.7 (0.3–1.2) | 0–12 | 0.5 (0.1–0.9) | 0–8 |

| Total work-related activities | 6.1 (5.6–6.6) | 0–11 | 5.5 (4.9–6.2) | 0–9 |

When asked about their activities the day before the interview, HEWs in intervention areas reported spending an average of 6.1 hours on work tasks. They spent an average of about 4 hours providing or offering clinical services in the health post, about 30 minutes providing clinical services in the community, and nearly 1 hour carrying out community mobilization/education activities. HEWs in comparison areas spent less time in health posts and more time in the community. Intervention and comparison health posts were reportedly open and offering clinical services for an average of about 20 hours in the previous week.

Discussion

Several countries and international agencies are pushing for rapid scale-up of iCCM, despite a dearth of evidence on best practices for implementation, quality of care, and impact. The scale-up of iCCM in Ethiopia is the most ambitious implementation of the strategy in sub-Saharan Africa to date. The country also has the advantage of a large literate, relatively well-trained, and salaried cadre of HEWs. Thus, it is important to take note of the lessons from the implementation of iCCM in Ethiopia for both improvement of the Ethiopia program and implementation in other countries as they prepare to scale up iCCM.

iCCM has largely been implemented as planned in the study areas. Nearly all HEWs were trained in iCCM, and 87% had received supervision in iCCM in the previous 3 months. Nearly 70% of health posts had all essential commodities for iCCM.

HEWs in iCCM intervention areas performed most basic assessment tasks and correctly managed nearly two-thirds of all children, with minimal overprescription of drugs. Comparisons of our results with other studies with similar assessment methods show that adherence to clinical guidelines seems to be at least as high for HEWs as for health workers at hospitals and health centers in Ethiopia.35 Quality of care provided by HEWs also compares favorably with performance in management of multiple childhood illnesses by CHWs in Malawi,21 Kenya,17 and Papua New Guinea.16 A recent review of studies of CCM of pneumonia in sub-Saharan Africa concluded that CHWs had difficulties with counting children's respiratory rate, correct classification and treatment of pneumonia, and overuse of antibiotics.22 We found that HEWs counted respiratory rates more accurately, correctly treated a higher proportion of children with pneumonia, and overprescribed antibiotics less than CHWs in the previous studies.

Despite these achievements, only about one-third of children with severe illness were correctly managed, which is consistent with prior research.17,36 An important reason for this result was that only about one-half of children needing referral to a health facility were referred by the HEW. Other studies have shown that many referred children never reached the referral facility or caretakers complied with referral only after substantial delays.37,38 Lack of transportation, cost of transportation, fees for care at referral facilities, and responsibilities at home can all discourage compliance with referral.39,40 The failure of HEWs to refer children with severe illness seen in this study may have been attributable to the fact that the HEWs did not believe the caretakers would comply, and therefore, they preferred to treat the children in the health post.

Studies from Pakistan have shown that CHWs can diagnose and treat severe pneumonia and that CCM of severe pneumonia can reduce treatment failures.41,42 However, more evidence is needed, especially from sub-Saharan Africa. Research is also needed on the reasons for mismanagement of children with severe illness and whether health outcomes can most feasibly and effectively be improved through enhanced training of CHWs on recognition of severe illness and danger signs, facilitation of transportation for referral, or enabling CHWs to treat children with severe illness in the community. Although mismanagement of children with severe illness is a serious concern, it should be noted that, even if referral rates are low, iCCM can still contribute to substantial reductions in mortality through the early management of illnesses, thus preventing children from becoming severely ill in the first place.

Few children accessed care from HEWs, and virtually no children under 2 months of age, the age group with the highest risk of mortality, were seen. Box 2 presents an estimation of the gap between expected and actual sick child consultations in intervention areas. Using the average number of consultations in the previous 1 month and the estimated number of children under 5 years old in the health post catchment area at surveyed health posts, there were 0.26 consultations at health posts per child per year. If we assume that patients should seek care from HEWs for 25–50% of illness episodes (a conservative estimate considering that HEWs are meant to be the primary source of care in the public health system and that care-seeking from other sources is low43), only 16–38% of expected consultations from HEWs were actually seen. More encouragingly, significantly higher use in intervention areas than comparison areas suggests that use may have increased where the iCCM program was introduced and services improved. Furthermore, there was a large range in the number of consultations in the previous 1 month, with several health posts registering two to three times the average. More research is needed to understand why some health posts have much higher use than others.

Box 2 Estimation of the gap between expected and actual iCCM consultations in intervention health posts in Jimma and West Hararghe Zones, Oromia Region, Ethiopia in 2012

Low use of child health services is a common challenge. It was seen in the multicountry evaluation of integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI), where improvements in quality of care were mitigated by low levels of care-seeking at health facilities and a failure to reach sick young infants (younger than 2 months old).44–46 Although CCM is meant to substantially increase access to care, uptake of community-based services is often disappointing. A global review of data on sources of care for sick children from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) in 42 countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia found that CHWs generally were not an important source of care.47

To earn the trust of the communities and attain greater uptake of services, program implementers must ensure consistent availability of health workers and essential commodities. Demand creation activities and increased active case detection by HEWs are also urgently needed. The experience of recruiting children for this survey suggests that there are large numbers of children with easy access to HEWs who fail to use their services despite being seriously ill. The Ethiopian Government's launch of the “Health Development Army,” for which up to 3 million community members will be mobilized nationally to serve as community health volunteers, presents a promising platform through which to carry out large-scale demand creation.48 However, a thorough evaluation of this new initiative is needed.

This study has a number of limitations. First, small sample sizes of children with malaria and measles precluded assessment of management of those illnesses. Second, HEWs may have performed better under observation than they normally would have performed.49,50 Third, informing HEWs of survey visits may have allowed them to prepare for the visits, which would have further biased the results positively. Fourth, recruitment and mobilization of sick children may have provided a sample of patients that was different from spontaneous patients, although concerns that we would obtain few children with severe illness proved unfounded. If these children were different from the children that the HEWs normally would see, it could have biased the results. Fifth, some information was based on self-report by HEWs, which may be biased. Sixth, iCCM program implementers knew which woredas were selected as intervention areas; therefore, extra effort may have been given to these areas, and implementation may have been stronger than in other areas of the country. Seventh, because the HEWs are a relatively well-trained and well-remunerated cadre of health workers, the results on HEW performance may not be generalizable to CHWs with a lower skill level and fewer incentives. These limitations may have resulted in observed levels of implementation strength and quality of care that were higher than they would have been under normal circumstances.

Scaling up iCCM at a national or regional level poses considerable challenges. The scale of the task of deploying CHWs and ensuring adequate training, sustained supervision, and availability of essential commodities can be daunting, but this challenge is well-recognized. The additional challenge of ensuring community demand for iCCM services is equally important but may be overlooked. Without concerted efforts to promote use of services, millions of dollars spent on implementation of iCCM may have little impact on child mortality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ato Shallo Dhaba and Dr. Zelalem Habtamu of the Oromia Regional Health Bureau and Dr. Luwei Pearson of the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) Ethiopia Country Office for their strong support of this research. Thanks to ABH Services, PLC for implementation of the survey. We also thank the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health, the JSI Research and Training Institute, Inc./Last 10 Kilometers Project (JSI/L10K), the Integrated Family Health Program (JSI/IFHP), and UNICEF New York for their support and assistance.

- 1.↑

Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Campbell H, Cibulskis R, Li M, Mathers C, Black RE, 2012. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 379: 2151–2161.

- 2.↑

Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS, 2003. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet 362: 65–71.

- 3.↑

Schellenberg JA, Victora CG, Mushi A, de Savigny D, Schellenberg D, Mshinda H, Bryce J, 2003. Inequities among the very poor: health care for children in rural southern Tanzania. Lancet 361: 561–566.

- 4.↑

Victora CG, Wagstaff A, Schellenberg JA, Gwatkin D, Claeson M, Habicht JP, 2003. Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: more of the same is not enough. Lancet 362: 233–241.

- 5.↑

Bhutta ZA, Chopra M, Axelson H, Berman P, Boerma T, Bryce J, Bustreo F, Cavagnero E, Cometto G, Daelmans B, de Francisco A, Fogstad H, Gupta N, Laski L, Lawn J, Maliqi B, Mason E, Pitt C, Requejo J, Starrs A, Victora CG, Wardlaw T, 2010. Countdown to 2015 decade report (2000–10): taking stock of maternal, newborn, and child survival. Lancet 375: 2032–2044.

- 6.↑

Ghebreyesus TA, Witten KH, Getachew A, O'Neill K, Bosman A, Teklehaimanot A, 1999. Community-based malaria control in Tigray, northern Ethiopia. Parassitologia 41: 367–371.

- 7.

Delacollette C, Van der Stuyft P, Molima K, 1996. Using community health workers for malaria control: experience in Zaire. Bull World Health Organ 74: 423–430.

- 8.↑

Dawson P, Pradhan Y, Houston R, Karki S, Poudel D, Hodgins S, 2008. From research to national expansion: 20 years' experience of community-based management of childhood pneumonia in Nepal. Bull World Health Organ 86: 339–343.

- 9.↑

Theodoratou E, Al-Jilaihawi S, Woodward F, Ferguson J, Jhass A, Balliet M, Kolcic I, Sadruddin S, Duke T, Rudan I, Campbell H, 2010. The effect of case management on childhood pneumonia mortality in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol 39 (Suppl 1): i155–i171.

- 10.

Baqui AH, Arifeen SE, Williams EK, Ahmed S, Mannan I, Rahman SM, Begum N, Seraji HR, Winch PJ, Santosham M, Black RE, Darmstadt GL, 2009. Effectiveness of home-based management of newborn infections by community health workers in rural Bangladesh. Pediatr Infect Dis J 28: 304–310.

- 11.

Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K, Bosch-Capblanch X, van Wyk BE, Odgaard-Jensen J, Johansen M, Aja GN, Zwarenstein M, Scheel IB, 2010. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD004015.

- 12.

Kidane G, Morrow RH, 2000. Teaching mothers to provide home treatment of malaria in Tigray, Ethiopia: a randomised trial. Lancet 356: 550–555.

- 13.↑

Sazawal S, Black RE, 2003. Effect of pneumonia case management on mortality in neonates, infants, and preschool children: a meta-analysis of community-based trials. Lancet Infect Dis 3: 547–556.

- 14.↑

WHO/UNICEF, 2012. Joint Statement: Integrated Community Case Management (iCCM). Geneva: World Health Organization and United Nations Children's Fund.

- 15.↑

de Sousa A, Tiedje KE, Recht J, Bjelic I, Hamer DH, 2012. Community case management of childhood illnesses: policy and implementation in Countdown to 2015 countries. Bull World Health Organ 90: 183–190.

- 16.↑

Rogers S, Paija S, Embiap J, Pust RE, 1991. Management of common potentially serious paediatric illnesses by aid post orderlies at Tari, Southern Highlands Province. P N G Med J 34: 122–128.

- 17.↑

Kelly JM, Osamba B, Garg RM, Hamel MJ, Lewis JJ, Rowe SY, Rowe AK, Deming MS, 2001. Community health worker performance in the management of multiple childhood illnesses: Siaya District, Kenya, 1997–2001. Am J Public Health 91: 1617–1624.

- 18.

Mukanga D, Babirye R, Peterson S, Pariyo GW, Ojiambo G, Tibenderana JK, Nsubuga P, Kallander K, 2011. Can lay community health workers be trained to use diagnostics to distinguish and treat malaria and pneumonia in children? Lessons from rural Uganda. Trop Med Int Health 16: 1234–1242.

- 19.

Kalyango JN, Rutebemberwa E, Alfven T, Ssali S, Peterson S, Karamagi C, 2012. Performance of community health workers under integrated community case management of childhood illnesses in eastern Uganda. Malar J 11: 282.

- 20.

Hamer DH, Brooks ET, Semrau K, Pilingana P, MacLeod WB, Siazeele K, Sabin LL, Thea DM, Yeboah-Antwi K, 2012. Quality and safety of integrated community case management of malaria using rapid diagnostic tests and pneumonia by community health workers. Pathog Glob Health 106: 32–39.

- 21.↑

Gilroy KE, Callaghan-Koru JA, Cardemil CV, Nsona H, Amouzou A, Mtimuni A, Daelmans B, Mgalula L, Bryce J, 2013. Quality of sick child care delivered by Health Surveillance Assistants in Malawi. Health Policy Plan 28: 573–585.

- 22.↑

Druetz T, Siekmans K, Goossens S, Ridde V, Haddad S, 2013. The community case management of pneumonia in Africa: a review of the evidence. Health Policy Plan, Epub ahead of print, December 25, 2013.

- 23.↑

Office of the Population and Housing Census Commission, 2011. Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census: Population Size by Age and Sex. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Population Census Commission.

- 24.↑

The World Bank, 2011. World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: Development Data Group, The World Bank.

- 25.↑

ORHB, 2010. Health Sector Five Year Plan (HSDP IV). Finfinne, Ethiopia: Oromia Regional Health Bureau.

- 26.↑

WHO, 2003. Health Facility Survey: Tool to Evaluate the Quality of Care Delivered to Sick Children Attending Outpatient Facilities. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development, World Health Organization.

- 27.↑

ICCM Task Force, 2003. CCM Central: Integrated Community Case Management of Childhood Illness. Available at: http://www.ccmcentral.com. Accessed May 3, 2013.

- 28.↑

Hartung C, Anokwa Y, Brunette W, Lerer A, Tsent C, Borriello G, 2010. Open Data Kit: tools to build information services for developing regions. Proceedings of the 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development (ICTD), December 13–16, 2010, London, United Kingdom.

- 29.↑

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG, 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42: 377–381.

- 32.↑

Rowe AK, de Leon GF, Mihigo J, Santelli AC, Miller NP, Van-Dunem P, 2009. Quality of malaria case management at outpatient health facilities in Angola. Malar J 8: 275.

- 33.↑

Gilroy KE, Callaghan-Koru JA, Cardemil CV, Nsona H, Amouzou A, Mtimuni A, Daelmans B, Mgalula L, Bryce J; CCM-Malawi Quality of Care Working Group; 2012. Quality of sick child care delivered by Health Surveillance Assistants in Malawi. Health Policy Plan 28: 573–585.

- 34.↑

Institute for International Programs, 2013. Catalytic Initiative to Save a Million Lives. Available at: http://www.jhsph.edu/dept/ih/IIP/projects/catalyticinitiative.html. Accessed June 10, 2013.

- 35.↑

Essential Services for Health in Ethiopia, 2008. Health Facility End-Line Survey: Synthesis Report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Essential Services for Health in Ethiopia.

- 36.↑

Cardemil CV, Gilroy KE, Callaghan-Koru JA, Nsona H, Bryce J, 2012. Comparison of methods for assessing quality of care for community case management of sick children: an application with community health workers in Malawi. Am J Trop Med Hyg 87: 127–136.

- 37.↑

Kallander K, Tomson G, Nsungwa-Sabiiti J, Senyonjo Y, Pariyo G, Peterson S, 2006. Community referral in home management of malaria in western Uganda: a case series study. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 6: 2.

- 38.↑

Starbuck E, Raharison S, Ross K, Kasungami D, 2013. Integrated Community Case Management: Findings from Senegal, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Malawi. Washington, DC: Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program, United States Agency for International Development.

- 39.↑

Peterson S, Nsungwa-Sabiiti J, Were W, Nsabagasani X, Magumba G, Nambooze J, Mukasa G, 2004. Coping with paediatric referral–Ugandan parents' experience. Lancet 363: 1955–1956

- 40.↑

Kallander K, Hildenwall H, Waiswa P, Galiwango E, Peterson S, Pariyo G, 2008. Delayed care seeking for fatal pneumonia in children aged under five years in Uganda: a case-series study. Bull World Health Organ 86: 332–338.

- 41.↑

Bari A, Sadruddin S, Khan A, Khan I, Khan A, Lehri IA, Macleod WB, Fox MP, Thea DM, Qazi SA, 2011. Community case management of severe pneumonia with oral amoxicillin in children aged 2–59 months in Haripur district, Pakistan: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 378: 1796–1803.

- 42.↑

Soofi S, Ahmed S, Fox MP, MacLeod WB, Thea DM, Qazi SA, Bhutta ZA, 2012. Effectiveness of community case management of severe pneumonia with oral amoxicillin in children aged 2–59 months in Matiari district, rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 379: 729–737.

- 43.↑

Central Statistical Agency, Ethiopia; ICF International, 2012. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Agency and ICF International.

- 44.↑

Armstrong Schellenberg JR, Adam T, Mshinda H, Masanja H, Kabadi G, Mukasa O, John T, Charles S, Nathan R, Wilczynska K, Mgalula L, Mbuya C, Mswia R, Manzi F, de Savigny D, Schellenberg D, Victora C, 2004. Effectiveness and cost of facility-based Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) in Tanzania. Lancet 364: 1583–1594.

- 45.

El Arifeen S, Blum LS, Hoque DM, Chowdhury EK, Khan R, Black RE, Victora CG, Bryce J, 2004. Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) in Bangladesh: early findings from a cluster-randomised study. Lancet 364: 1595–1602.

- 46.↑

Bryce J, Victora CG, Habicht JP, Black RE, Scherpbier RW, 2005. Programmatic pathways to child survival: results of a multi-country evaluation of Integrated Management of Childhood Illness. Health Policy Plan 20 (Suppl 1): i5–i17.

- 47.↑

Hodgins S, Pullum T, Dougherty L, 2013. Understanding where parents take their sick children and why it matters: a multi-country analysis. Glob Health Sci Pract 1: 328–358.

- 48.↑

Admasu K, 2013. The implementation of the Health Development Army: challenges, perspectives and lessons learned with a focus on Tigray's experience. Policy and Practice: Federal Ministry of Health, Addis Ababa 5: 3–7.

- 49.↑

Rowe AK, Lama M, Onikpo F, Deming MS, 2002. Health worker perceptions of how being observed influences their practices during consultations with ill children. Trop Doct 32: 166–167.

- 50.↑

Leonard K, Masatu MC, 2006. Outpatient process quality evaluation and the Hawthorne Effect. Soc Sci Med 63: 2330–2340.

- 51.

Rudan I, O'Brien KL, Nair H, Liu L, Theodoratou E, Qazi S, Luksic I, Fischer Walker CL, Black RE, Campbell H, 2013. Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia in 2010: estimates of incidence, severe morbidity, mortality, underlying risk factors and causative pathogens for 192 countries. J Glob Health 3: 10401.

- 52.

Fischer Walker CL, Perin J, Aryee MJ, Boschi-Pinto C, Black RE, 2012. Diarrhea incidence in low- and middle-income countries in 1990 and 2010: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 12: 220.

- 53.

Yewhalaw D, Getachew Y, Tushune K, Michael KW, Kassahun W, Duchateau L, Speybroeck N, 2013. The effect of dams and seasons on malaria incidence and anopheles abundance in Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis 13: 161.